Organizations are immensely complicated social structures whose engines run on human creativity and effort. As a consequence, diagnosing what is and isn’t working as intended can be incredibly complicated. This high degree of complexity is, in fact, why we developed the Flow@Work model of engagement. We believe, based on review of the available evidence, that engagement is at the core of understanding how well the processes and structures of a given business are working for those who work within it.

However, every organization has a unique history and character, which both creates the basis for their competitive edge in the marketplace, and also creates a host of problems which are distinctive to each particular organization. Being unique, while critical to success, means that there is rarely an instruction manual for how to respond to a given problem within the organization.

This is why developing a solution-oriented survey research process for your organization is critical. If done well, a customized survey process provides a lens for evaluating aspects of organizational experience that may be overlooked as part of day-to-day activities. Just like glasses, however, if the survey process is poorly customized to the organization, our ability to perceive what is going on with the organization is often distorted or insufficiently focused.

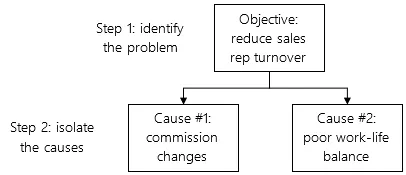

Given the need to address unique organizational problems, here is a quick rundown of what to keep in mind when customizing solution-oriented surveys. This will involve 3 key steps.

- Identifying the Problem – Setting an Objective

- Isolating the Causes – Establishing Facets

- Asking the Right Questions – Simplicity & “Non-trasts”

Step 1: Identifying the Problem – Setting an Objective

Just like problems that we face in our day to day lives, sometimes figuring out that something is going wrong is incredibly simple. The problem basically shouts out to us, “OUT OF MILK!” or “TURNOVER IS INCREDIBLY HIGH FOR SALES REPS!”. Other times, the problem is more subtle, and arises out of careful consideration of the challenges an organization faces. Either way, the obviousness of the effects of the problem are not an indication of the simplicity of figuring out the causes of those problems. Traffic congestion, as an example, is an amazingly obvious problem, which has a whole host of complicated causes.

The goal to set for customized survey research then should be a more thorough understanding of the likely causes for the effects that you wish to change. For our example of high turnover for sales reps, high turnover is the effect and our response to that effect is seeking to lower those turnover numbers. From there, we can proceed to ask what is driving those effects.

Step 2. Isolating the Causes – Establishing Facets

Once we have an idea of the effects that we are trying to understand, and eventually solve, we can proceed to trying to diagnose underlying causes. This is the most, for lack of a better term, creative part of developing customized surveys. Given this, it relies on your ability to consider the information available to you and make judgements on the usual contributors for the problem at hand. In the case of high sales rep turnover, for example, you can use your knowledge of recent events within the organization (e.g., recent adjustments to the commission system, or new leadership) to come up with possible explanations for the problem at hand. Further, you can also do research on the causes of similar problems within other organizations.

The goal at this step of the process, however, is not to identify the cause; the goal is to create a list of possible causes. Given this goal, brainstorming a variety of possible causes with a group of involved employees can also be of value. After you have gathered a large number of possible causes, you can then start grouping those causes together, based on similarity, and homing in on the causes that you think are most central to producing the problem at hand. The goal in this step is to consider a large number of possible causes, and then to narrow it down to causes that you and your team believe are both likely and addressable.

These causes then form the facets of the problem that you will investigate with the questions you develop for the survey.

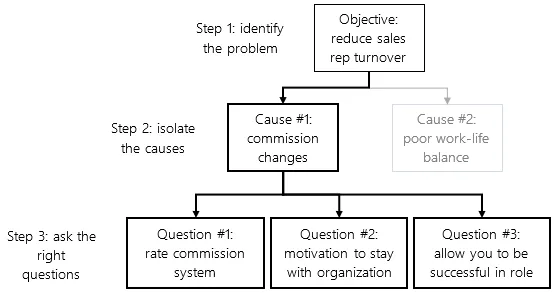

Step 3. Correctly Asking the Right Questions – Simplicity & “Non-trasts”

Although listing out the possible causes of a problem itself can be extremely useful, nothing beats data. Collecting good data allows us to move from a list of well-considered opinions on what is going wrong, to a set of facts used to establish what is causing the mess.

To do so, you will need to further deconstruct each of the facets into a discrete set of questions that members of your organization can respond to. This means that your questions must be as simple as possible to read, cover a single very specific topic, and relate to the facet the question intends to address.

Turning back to our example of a high sales rep turnover, a bad question for a facet concerning commission would be:

“Do you think that the changes to the commission structure had a harmful effect and resulted in increased turnover?”

This question is bad for a variety of reasons. Chief among them is that it's unclear to the reader what a “harmful effect” is. Similarly, this question also bundles too many options together. Some sales reps could think that the changes to commission structure had a positive effect, while also believing that it resulted in higher turnover. The rated responses you would get to a question like that would be all over the place. In essence, this question asks too much of the reader given that they are generally going to be responding with a 1-5+ scale number. This question also asks the employee about something they would not even have good insight on, namely, the experience of other people in the organization. Instead, good survey questions ask people about something they are experts on: their own experiences.

Instead of complicated questions, we want multiple extremely straightforward questions on a single given facet. As a rule of thumb, you do not want any fewer than 3 questions for a given facet. Not only will your data analyst thank you but doing so sets up what I like to call “non-trasts” for each facet. Said another way, asking the same question in different ways should provide similar results for each of the similarly asked questions. This serves as a check for whether responses to these questions provide a clear insight into the problem at hand. As to why you need at least 3 questions for this check to work, consider how much easier it is to decide which thermometer is broken when you have 3 on hand, as opposed to 2.

A better way to get at the ideas that the above bad question is asking, would be to break it into 3, as below:

- How satisfied are you with the new commission system?

- To what degree does the new system motivates you to stay with this organization?

- Do you believe that the new commission system allows you to be successful in your role?

Each of these questions asks the individual directly about their personal experiences, and only contains a single topic of interest directly related to the facet in question (e.g. Does the new commission system affect sales rep turnover?). The results to each of these questions can then be compared to the results observed from other facets. If the results for this particular facet suggest that the sales reps are basically neutral or positive on the topic of the new commission system, you have a pretty strong indication that it is unlikely to be the cause.

You would then repeat a similar question writing process for the rest of the facets that you judged to be meaningful. One of the big limiters on the facets that you consider as part of your customized survey research process is likely to be the amount of questions you think the employees are willing to respond to. No one wants to feel like they are wasting time (especially sales reps!), so be sure to take that into account as you consider which facets you can practically address as part of the survey process.

Once you have decided on your objective for the survey process, the possible causes of the problem at hand, and the questions you would like to use to decide on which of those facets is likely the root cause, you are ready to begin the survey process! You can even go a step further in making customized survey research a painless as possible by using a platform which supports you every step of the way.

If you would like to learn more about what to do once you started getting responses, check out our 3-part series on what to do after you have done an engagement survey:

Part 1: Contextualize the Findings

Part 2: Evaluate Possible Responses

Part 3: Develop Key Questions for Follow-up Surveys

Although this guide was written with engagement in mind, many of the recommendations can be applied to any organizational survey research. If you don’t have the time to read through all of that, feel free to